Le Grand Tour

Le Grand Tour wasn’t Plan A. It wasn’t even Plan B. It was more of a Plan C. Yet in no way did it turn out to be a third-rate cycle. 5,000 km from Hook of Holland to Hook of Holland via the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Switzerland, Austria and Germany in the summer of 2022.

By the early months of 2020 I was busy planning a six-week trip from the northernmost point of Japan at Cape Sōya to the country’s southernmost point at Cape Sata. But COVID-19 happened…

I came up with a Plan B, to cycle around the Baltic Sea following the route of EuroVelo 10 - Baltic Sea Cycle Route. It lacked, however, one key ingredient: my enthusiasm. The war in Ukraine also threw up logistical problems involving Russia and its exclave of Kaliningrad. However, with a ticket already purchased for the Hull to Rotterdam ferry for the evening of 2 July, were there other options? The most obvious was to turn right upon arrival at Rotterdam, not left. Plan C had been born.

Putting Plan C on the map… not without doubts

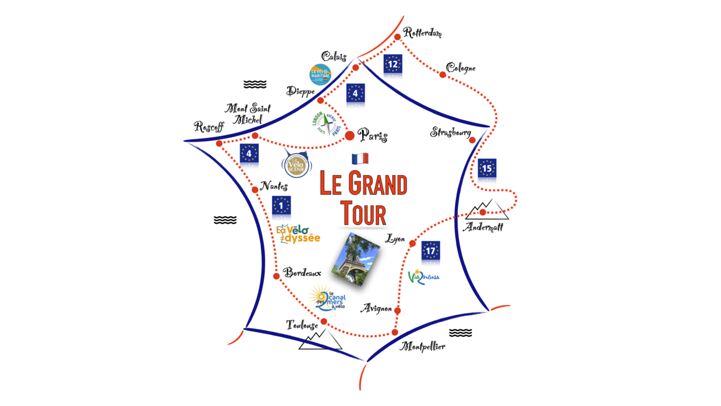

Although I have a reputation as being (as I was once introduced at The Cycle Touring Festival) ‘Mr Cycling Europe’ there are many iconic routes in Europe that I have never cycled in their entirety; the Avenue Verte to Paris, the Vélodyssée along the west coast of France and EuroVelo 15 - Rhine Cycle Route to name just three. Could my Plan C be an opportunity to plug some of these gaps in my cycling knowledge? I pored over the map and attempted to piece together a route.

By turning right at Hook of Holland I could follow EuroVelo 12 - North Sea Cycle Route to Calais and the Vélomaritime (EuroVelo 4 - Central Europe Route) to Dieppe. Here I could head south in the direction of Paris along the French section of the Avenue Verte, the route linking the British and French capitals. A route I’d never before heard of - the Véloscénie - connected Paris with Mont Saint-Michel, where I could rejoin the Vélomaritime as far as Morlaix in Brittany. From there I could follow the northern portion of the Vélodyssée (EuroVelo 1 - Atlantic Coast Route) to Royan where the Véloroute Des 2 Mers A Vélo could take me to the Mediterranean via Bordeaux, the Canal de la Garonne, Toulouse and the Canal du Midi. EuroVelo 17 - Rhone Cycle Route, called the ViaRhôna in France, could be followed from Sète to Andermatt, high in the Swiss Alps where, rather conveniently, the Rhine Cycle Route could return me to The Netherlands, Hook of Holland and my ferry back home on 3 September. That didn’t seem too shabby for a Plan C.

Was it, however, feasible? I had a very tight deadline – only nine weeks before I went back to the school where I teach - so I came up with a slightly modified Plan C: I would use a maximum of ten trains, each of no more than 100 km, to make it realistic. It was a wise move and my journey was no less epic as a result. My average daily cycle would now be a much more cyclist-friendly 80 km per day.

Off I go!

In my Grand Tour, perhaps 80% of the journey was traffic-free although that figure was probably closer to 100% in the first week or so of the trip as I cycled along the coasts of the Netherlands and Belgium. When I arrived in France, most of the cycling was well away from major roads with cycle paths adopting the narrow lanes of the French countryside if there wasn’t a disused railway or canal towpath at hand. The French cycling authorities have done a commendable job in recent years in developing their medium and long-distance cycling routes. Along with their distinctive - enticing even - names (La Scandibérique, La Vélo Francette, La Route des Grandes Alpes…), each has unique branding, is well signposted and has a wealth of information available online via dedicated websites. This was certainly the case with the six French routes that I adopted; La Vélomaritime (the French section of EuroVelo 4), L’Avenue Verte, La Véloscénie, La Vélodyssée (the French section of EuroVelo 1), Le Canal des 2 Mars A Vélo and ViaRhôna (the French section of EuroVelo 17). The national website, FranceVeloTourisme.com, is the best place to start your planning.

Cycling south from Dieppe along the Avenue Verte, I did think I had discovered a disused railway line that couldn’t be surpassed in terms of its quality and what it provided for the travelling cyclist. Aside from the quality of the route itself (no potholes here), there were regular opportunities to pause and eat in the cafés that had moved into the disused railway stations, often having basic bicycle maintenance facilities available. Yet the experience would be repeated over and over again as I continued on my long loop around France. There were several such abandoned railways linking Paris with Mont Saint-Michel, more along the Vélodyssée and, when leaving Bordeaux, I followed the superb Voie Verte Roger Lapébie linking the great city of wine to the Canal de la Garonne some 40km to the south-east. Many of these disused railway lines have been officially adopted as departmental roads (without cars). This requires the local authorities responsible for them to maintain them to a high standard. If only that were the case nearer to home… Combined with the canal towpaths, much of my cycle came courtesy of the toil of hardworking navvies of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

Back in Paris, making use of the compass on my handlebars, I eventually arrived at Notre Dame in time to make it to my Warmshowers host’s flat in the nearby Marais district. He proved to be an excellent host giving me a guided tour of the 4th arrondissement and fascinating insights into the changing face of his corner of Paris. I had equally memorable Warmshowers experiences on a co-housing project near Ostend, with a wonderfully welcoming non-cyclist in Agen (she had stumbled upon a lost cyclist in the street a couple of years previously and had been taking them in ever since) and even attended a birthday party with the extended family of a sprightly 78 year-old in Sierre, Switzerland. Most nights were, however, spent in the tent and I’m delighted to report that, despite reports to the contrary, the French municipal campsite is alive and kicking.

EuroVelo 17: a hidden gem

I had few expectations for the ViaRhôna – aka EuroVelo 17. At the planning stage it was the part of the journey that simply linked two other places where I wanted to be; the Mediterranean and the Alps. It turned out to be the highlight of the entire trip. I lost count of the number of bridges that I crossed but at 8am one morning, under a blue sky and with not another soul in sight, crossing the rebuilt suspension bridge near Rochemaure was a magical experience. Destroyed several times over its lifetime it has now found a fitting purpose in transporting pedestrians and cyclists across the River Rhône. Just one of many memorable moments.

After Lyon, the ViaRhôna took my route in the direction of Switzerland and mountains became a feature of the cycle for the first time. That said, it wasn’t until after several days cycling in Switzerland that the major physical challenge of the cycle presented itself: the climb to the Furka Pass at 2,436 metres. Following in the tire tracks of Sean Connery in his Aston Martin in Goldfinger, it was a long climb but rewarded with Alpine views and a long descent into the valley to Andermatt.

Back to my starting point on EuroVelo 15 – Rhine Cycle Route

My onward journey along the Rhine required another climb to the Oberalppass, but having just earned my spurs at the Furka Pass, I chose to take one of my trains. It was train number eight of the trip. The previous ones had been chosen for a variety of reasons; to make progress (Calais to Le Touquet), avoid suburbs (Paris to Chartres), to relieve the boredom of cycling along the Nantes-Brest Canal (Redon to Couëron)… But here in Switzerland it was because I fancied taking one of the little red trains that had been passing me along the Swiss valleys for days.

From the Oberalppass it was, literally, downhill all the way as I headed east through Switzerland before swinging west and then north along the Rhine. Time began to play on my mind. I left Andermatt on 23 August so I had just 12 days to get back to Rotterdam, Hook of Holland and my ferry home. The two remaining trains helped, as did a ferry on the Bodensee from Bregenz to Konstanz (after drinking far too much beer with a German friend I’d met up with for lunch) but I wasn’t confident of completing the loop on time until the very end of August and it did require some long days in the saddle. But where better a place to spend hours in the saddle than back in the cycling nirvana of the Netherlands. I reached the sign at Hook of Holland in the mid-afternoon of 3 September. My ferry back home to Yorkshire departed at 8pm that evening and I was back in the classroom just 36 hours later…

The book should be available to read in 2024 but if you can’t wait until then, listen to episodes 52 to 59 of The Cycling Europe Podcast. They were all recorded, edited and published during the cycle. There are also four films to watch on YouTube. All the links can be found by visiting CyclingEurope.org/LeGrandTour.

Article by Andrew P. Sykes

The original version of the article appeared in CyclingUK Magazine. Edits have been made.